Listening Across Worlds: Weaving Justice Through an Implementation Project in Argentina

María Florencia Blanco Esmoris is an anthropologist (PhD, Universidad Nacional de San Martín – UNSAM) and a researcher at the Centro de Investigaciones Sociales (CIS-CONICET/IDES-UNTREF). Her applied anthropology work bridges research, public policy, and collaboration with community organizations and institutional actors. She teaches Applied Anthropology and Qualitative Methods. Throughout her career, she has been consistently invited by community and non-governmental organizations for her methodological expertise and her skill in producing rigorous, context-sensitive systematizations.

Affiliation

Centro de Investigaciones Sociales (CIS-CONICET/IDES-UNTREF)

Keywords

Listening; justice; project implementation; applied anthropology; migration; trust-building

Methodological Takeaway:

Applied ethnography strengthens policy implementation by enabling translation between global accountability frameworks and local realities, making visible forms of coordination, care, and trust-building that are essential for effective and ethically grounded interventions but often remain invisible in standard M&E systems.

Introduction: Landing on an Implementation Project

What does ethnography look like when global agendas encounter local worlds? In what follows, I attempt to address this question from my own situated experience. The very month I completed my PhD viva voce, I stepped into a professional world I had only encountered from its margins. I began working in the Monitoring and Evaluation Area of a Latin American NGO with an office in Argentina, where I was hired to coordinate research and publications.[1] Until then, my knowledge of the “third sector” (that is, non-profit organizations) came from sporadic collaborations through community projects and university outreach initiatives.

My entry into the NGO gradually ushered in a different orientation altogether, as over time and through occupying diverse positions, I was pushed to shift from my traditional academic everyday practice (marked by a largely solitary fieldwork for my own research, self-directed ethnographic inquiry, preparing conference papers, tutoring students, teaching, writing, and engaging in theoretical debate) to a more practical one (collaborative thinking and decision-making, collective project implementation, predefined timelines and straight deadlines, reporting obligations, performance indicators, and multiple layers of accountability).

Although I formally entered the organization as research coordination, while also collaborating in an external audit, the scope of research coordination already encompassed a broad set of responsibilities. These included the recruitment and contracting of field researchers, the supervision and follow-up of their fieldwork and outputs, the assessment of which materials were suitable for publication, and the initiation of the NGO’s first indexed publication line. In parallel, I was responsible for systematizing the NGO’s social implementation processes and accompanying territorial teams interested in developing their own research initiatives.

Within this fluid institutional landscape, in 2022, I joined an ongoing international initiative that would reshape my understanding of applied anthropology. During this period, a colleague left the NGO and given my prior direct involvement in the project -particularly in relation to territorial research and qualitative strategies- I had become the second person inside the Monitoring and Evaluation area most familiar with its design and implementation. As a result, I began to assume the role of Monitoring and Evaluation Officer (M&E Officer) for the project’s implementation in Argentina.

Until then, my understanding of the role was largely observational, based on watching two colleagues perform similar functions: one in this project and another in a different one implemented in other provinces of Argentina. I knew it involved weekly meetings with the donor and other stakeholders, strict adherence to a Comprehensive Monitoring and Evaluation Plan (CMEP) manual, and the production of periodic reports.

What was this project about? It was a large-scale project addressing labor exploitation, including child labor (CL), forced labor (FL), and human trafficking (HT), aimed at strengthening laws and enforcement mechanisms and improving coordination among state agencies, civil society organizations, and other key stakeholders. The initiative was funded by a Global North government agency and implemented across Asia, Africa, and Latin America by an international development organization and its partners. In Argentina, our NGO was one such implementation partner. Given the NGO’s longstanding engagement in local community development, my role offered a vantage point from which to assess the tensions, translations, and negotiations of implementing an international vision and objective in a specific context.

Before I joined the team, the project began with a rapid assessment to ground and inform implementation. This rapid assessment provided an initial diagnosis of the local context, examining prevalence and characteristics of CL, FL, and HT in Argentina. The study identified the garment sector as a critical hotspot where various forms of precarious labor converge. This diagnosis became particularly evident when examining the dynamics surrounding one of South America’s largest informal markets, an emblematic commercial hub known as La Salada Fair[2]established in the early 1990s that draws migrant workers and families, primarily from Bolivia and Peru, into the textile and apparel economy. In its surrounding neighborhoods, numerous small- and medium-scale sweatshops operate under highly informalized and often exploitative conditions.

These initial findings set the stage for the implementation design that unfolded once I became directly involved in the project. At the time of my entry, an extensive fieldwork process was already underway, led by a territorial researcher examining how labor exploitation affected migrant populations in areas surrounding La Salada. I was familiar with this research through my parallel role, which involved the qualitative follow-up of ongoing fieldwork. In addition, key decisions regarding the articulation of actors for the project’s implementation in Argentina had already been defined by the project coordination.

In this setting, my role was to document each stage of the project, ensure systematic follow-up of objectives, indicators, and expected results, and maintain regular communication with the project coordinator. I was also responsible for briefing the project coordinator on progress related to indicators and targets, liaising with the global Monitoring and Evaluation team, and preparing periodic reports, while ensuring full compliance with the CMEP requirements -including best practices for data clarification, storage, and traceability, as well as ethical principles guiding the collection of relevant information.

This task of reporting required a genuinely multi-level approach that engaged a range of actors and institutions. Reporting on activities, expectations, and how they constituted incremental steps toward the proposed objectives and associated outcomes proved particularly challenging. In this sense, periodic reports not only documented what had been done, but also sought to demonstrate how specific forms of coordination and engagement advanced the project’s broader goals. Both the global Monitoring and Evaluation team and the global project coordination needed to grasp the significance of these processes.

One illustrative example of this challenge involved rendering visible forms of coordination that did not immediately appear as such. Documenting sustained dialogue and accompaniment with the management of childcare spaces in areas surrounding La Salada was not always recognized as a core coordination activity. These spaces were often managed by migrant women, some of whom had previously worked in sweatshops or had themselves been part of the garment sector. Yet the lack of safe, non-stigmatizing, and public childcare facilities meant that many women continued to work in sweatshops alongside their families. The possibility for families involved in the garment sector to access these spaces, where children were otherwise part of the productive scene, enabled the creation of care arrangements that sought to remove children from labor landscapes. Making these everyday infrastructural and care-related constraints legible in formal reporting frameworks became a key part of my work.

In this experience, I had not foreseen how intricate methodological and ethical entanglements would become in a project of this scale, entanglements that quickly grew both intellectually demanding and personally transformative. I found myself practicing anthropology not in a classroom or a traditional field site, but in the shifting terrain of an implementation process.

Navigating these layers of governance and partnership needed an anthropological sensibility attuned to how actors communicate, mistrust, negotiate, and imagine solutions within structurally unequal conditions. The work unfolded at temporalities that rarely aligned with the expectations of global administrators: processes moved slowly, dialogues needed repeated returns, and relationships grew through shared stories, pauses, and silences rather than through linear milestones.

This article examines how ethnographic skills were mobilized throughout the project, showing how ethnography offered opportunities for relational justice as part of an implementation process shaped by inequality, informality, and competing agendas.

Rather than approaching implementation as a purely technical endeavor, I situate it within a broader tradition of anthropological practice that takes the tensions between research, politics, and institutional action: a praxis that is attentive to the human, and therefore affective and ethical, dimensions of technical work and is itself never free from epistemological frameworks (Moya 2016). From this perspective, implementation and M&E are analytically distinct yet practically entangled. Implementation refers to the situated practices through which projects are enacted on the ground—coordination, negotiation, and everyday decision-making—while M&E designates the institutional apparatus that renders these practices legible through indicators, reports, and accountability frameworks. In practice, however, M&E was interwoven with implementation, actively shaping how activities were planned, adjusted, and justified over time, even as implementation realities repeatedly exceeded and challenged standardized evaluative categories.

In this interface, ethnography functioned as a connective praxis rather than a discrete methodological add-on. Ethnographic sensibilities informed implementation by foregrounding relational dynamics, care infrastructures, and power asymmetries that shaped how interventions unfolded in specific territorial contexts. At the same time, ethnography proved central to M&E by enabling forms of coordination, relational labor, and everyday constraints to be translated into reporting formats, while also exposing the moral framings and implicit hierarchies embedded in Global North development agendas (Mosse 2005). In doing so, ethnography opened spaces for relational justice within implementation processes shaped by inequality, informality, and competing institutional expectations.

1. A Situated Beginning:

Local Expertise and the Ethics of Embedded Knowledge

Although the project’s overarching outline had been designed by an international organization headquartered in the Global North and coordinated through a transnational implementation structure, its local articulation depended on understanding and tailoring efforts to the local context –interpreting subtle forms of social organization, kinship-based sweatshop arrangements, gendered divisions of labor, and tacit norms that sustained both precarious forms of labor and exploitation– which necessitated community engagement.

As pointed out, the Argentine Office of the NGO offered an essential vantage point for exploring the complexities. Its legacy included collaborations with local leaders in Ecuador and Peru on education and childhood initiatives, followed by longstanding health projects in the Ecuadorian Amazon. This history cultivated an institutional culture shaped by close community engagement and by the ability to work across diverse actors and interests. While anthropological perspectives were not entirely new to the organization—the director of the Argentine office was an anthropologist, and the head of the Monitoring and Evaluation area, held a master’s degree in anthropology— but what I brought to the project was extensive ethnographical and territorial experience and prior technical work with populations similar to those residing in the areas surrounding La Salada. This knowledge allowed my ethnographical practice to function as a particularly grounded resource, informing how local dynamics were interpreted and how implementation strategies were adjusted in response to shifting community realities.

One key intervention for this community engagement was the facilitation of collaborative mapping exercises; this cartographic component became central to building trust, facilitating dialogue, and producing shared knowledge. The process was led by an experienced cartographer with a strong background in cartographic theory, who had previously trained the project’s technical and territorial teams. In addition, the process was supported by a specialist in collective and community cartography with a background in dramaturgy, whose facilitation skills were crucial for sustaining participation and dialogue.

Together with community members, local actors, government personnel, and the project coordination team, and in collaboration with a graphic artist, we worked to co-construct categories, identify roles within the garment sector, and develop visual and spatial representations that more accurately reflected the daily realities of workshop life and migrant trajectories, where domestic and labor scenes often coexist in the same physical space. Rather than relying on standardized pictograms, we deliberately developed a shared symbolic system rooted in the garment sector and its specific working conditions.

A key strength of this process was working with territorial liaisons who had themselves been part of the garment industry and shared a common language and experiential knowledge with participants. These liaisons played a central role in convening women to an initial stage of pictogram development that preceded the collective mapping sessions in the territory. This preliminary phase focused on discussing the productive chain and its different links, while jointly identifying potential risk situations and everyday scenes in the sector. During these sessions, scenes were collectively described and discussed, and participants agreed together on how they would be symbolized, while a graphic artist produced visual notes in real time.

This pictogram-making process was particularly significant in exchanges with women -many of whom had experienced complex and often violent situations- where speaking through words alone proved difficult. Working through symbols and maps opened alternative windows for expression, while simultaneously demanding forms of attentive listening from all participants. In this sense, cartography operated not only as a representational device, but as a relational medium through which silences, affects, and embodied experiences could be acknowledged and engaged.

I participated in documenting the cartographic process to support systematization and to position mapping not only as a diagnostic tool, but also as a strategy for interinstitutional coordination: a space in which diverse actors encountered one another, co-produced knowledge, and developed a shared language that later facilitated coordinated action. In this sense, the collective development of symbolism stands out as a key moment in which listening was materially enacted, enabling the articulation of worlds often presumed to be disjointed.

This process was not merely technical. It involved negotiating meanings, revising assumptions, and identifying which elements of everyday life needed to be rendered visible. Cartography thus functioned as a collaborative method for coordinating across institutions, illuminating informal geographies, and making legible the lived experiences of migrant families.

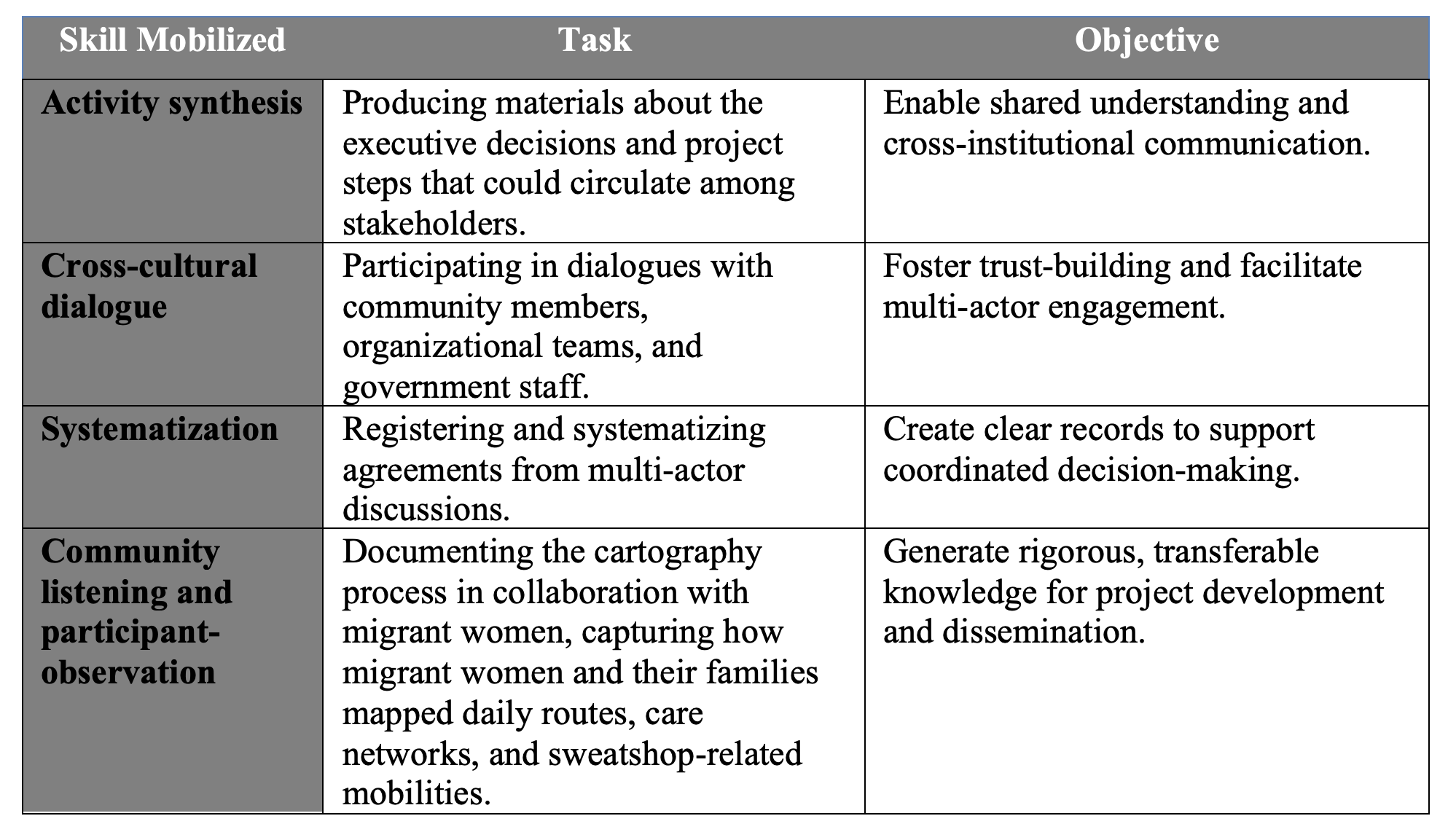

Within this landscape, my role required a combination of tasks. Meetings, interviews, and field visits became spaces for listening across layers of vulnerability, while the need to translate community perspectives into global reporting formats demanded careful ethical and analytical choices. The process underscored the centrality of trust-building concern at the very heart of anthropological practice. Trust is what makes it possible for people situated differently in power, geography, and institutional mandate to speak honestly, to listen across asymmetries, and to engage in forms of collaboration that exceed formal project requirements. As part of the intervention, this slow, relational work enabled participants and implementers to articulate concerns that rarely surface in official settings, opening space for shared understandings to take shape (see Table 1).

Table 1. Skill-Task Matrix

Source: Author’s Elaboration

2. The Everyday Labor of Making a Global Project Legible

Working at the intersection of international standards and everyday migrant life required continuous movement in both directions: interpreting global categories through local experience and simultaneously translating situated narratives back into formats intelligible to global reporting regimes.

2.1 Translating Global to Local

On the one hand, translating global categories into local realities proved challenging. Terms such as child labor, risk mitigation, or capacity strengthening often sat uneasily within the lived realities of migrant workers. Ethnographic engagement allowed these categories to be reinterpreted through everyday life: How could “vulnerability” be described without reinforcing stereotypes or diminishing agency?

Through sustained dialogue with local actors, these concepts were gradually reframed to reflect actual conditions, allowing interventions to remain accountable to global requirements while grounded in local experience. For many Bolivian and Peruvian families, kinship obligations, gendered expectations, and household survival strategies within the sweatshop economy were inseparable from precarious labour conditions, not because they lacked the desire to improve their situation, but because they were operating within the very narrow contexts where crafting a viable present and future remained possible at the precise point where structural inequalities converge.

2.2. Translating Local to Global

On the other hand, translating local narratives into global reporting requires an explicitly ethnographic sensibility. Turning field encounters into reports involved rendering situated negotiations, shifting household economies, and complex forms of relational labor into the structured categories expected by donors and international partners. This process demanded careful balancing: representing the nuance of lived experience while producing documents that met institutional expectations for clarity, comparability, and measurable progress.

This work echoes the applied anthropological insights of Holmes (2013) and Hale (2008), showing how other forms of institutional ethnography can open small but significant spaces for recognition, accountability, and justice within transnational development frameworks.

3. Four Moments of Applied Ethnography in a Transnational Project with Local Implementation

To illustrate how ethnographic practice shaped implementation, I present four moments from the field that reveal how listening, observation, and collaboration became essential tools for piloting a complex intervention.

3.1 Building Trust with Migrant Community

When a government inspection triggered widespread fear in neighborhoods associated with sweatshop production, many migrant women stopped attending community activities, concerned about the potential immigration-related consequences. From the perspective of the NGO, the project coordination team, and my own, we understood and acknowledged that informal conversations, such as chatting with women in kitchens, courtyards, and childcare centers, were often more valuable than conducting formal interviews with each woman.

Engaging in conversations that were not structured as interviews and did not interrupt women’s daily activities proved crucial. These everyday settings became niches of certainty, and therefore spaces of trust, where women felt able to speak, listen, and share experiences with others. Community listening made it possible to recognize emotions: fear, exhaustion, uncertainty, that technical protocols routinely overlook. These encounters shaped safer, slower, and more responsive ways of engaging with migrant households and sweatshop dynamics.

3.2 Rethinking “Capacity Building” with Institutional Authorities

From a labor-oriented perspective, institutional engagement with sweatshops was marked by a predominantly controlling and punitive gaze, one that targeted both working conditions and the precarious citizenship status of those employed within them. Throughout the project, conversations with different state agents, including judicial actors, revealed how their language encoded social, spatial, and symbolic distance from the ways migrant workers conceive of labor, survival, and inequality. Their reluctance to adopt new approaches stemmed less from unwillingness than from structural constraints: limited training, scarce resources, and contradictory mandates. The systematization of project information, including success stories, accounts of adverse experiences, and follow-up of two cross-cutting studies on migrant access to rights, opened space to propose adjustments to the coordination team on how to strengthen the bridge between institutional goals and lived realities. The ethnographic perspective that guided this documentation work–through detailed minutes, recorded conversations, and fieldnotes regularly shared with local counterparts–directly contributed to redesigning the training sessions developed by the project coordinator, shifting them away from abstract legal principles and toward concrete scenarios rooted in everyday conditions. Several agents later emphasized that hearing women’s narratives and also understanding how their lives were organized around sweatshops had been crucial for rethinking their own approach.

3.3 Reframing “Risk” Through Women’s Embodied Labor in Sweatshops

Negotiating the meaning of “risk” within sweatshops requires centering the experiences of the women whose labor, with their hands, their bodies, and their machines, sustains the daily functioning of these spaces. These women do not reject the language of risk because they fail to understand potential harms to their children; rather, they navigate risk as part of a broader strategy to secure livelihoods for their families. Their productive and reproductive labor is deeply intertwined, as caregiving tasks are brought into the sweatshop and woven into the rhythms of sewing. This creates a double burden shaped by migrant trajectories that are often informal and mediated by multi-layered conditions enabling their mobility. Understanding risk from this perspective reframes it from a moralized category into a situated, relational practice through which survival itself is continuously negotiated.

3.4 Working with Migrant Community Leaders

Instead of approaching community leaders as beneficiaries, we invited them to co-design training materials. Their stories revealed everyday forms of resistance, care, and mutual support rarely captured in official frameworks. Integrating their perspectives reshaped several program outputs and fostered a more horizontal, dialogic form of collaboration, an approach that resonates with Lassiter’s call for a collaborative ethnography grounded in shared authority and co-produced knowledge (Lassiter 2005). This collaborative process also informed the design of initiatives aimed at formalizing labor in the garment sector, protecting workers from child-labor practices, and promoting the development of care-oriented community spaces. As part of this work, we also facilitated knowledge transfer on how to document internal meetings and produce minutes among workers in caregiving spaces where migrant women connected to the sweatshops left their children, strengthening local capacities for collective organization and record-keeping.

4. Conclusions: Stitching Shared Understandings

Across the project, the sensibilities of cultural anthropology and the ethnographic approach proved less a vehicle for “giving voice” than a practice of cultivating encounters, opening spaces in which actors could genuinely listen to one another across institutional, social, and geographic divides. This approach resonates with broader conversations in applied anthropology in Latin America, where scholars have argued that the field becomes transformative when it shifts from instrumental problem-solving to sustained ethical engagement. As Moya (2016) suggests, applied anthropological work is always shaped by underlying assumptions about how knowledge is produced and what counts as evidence—assumptions that become visible only in practice. Applied research requires grappling with the implicit logic embedded in development programs, especially when these programs are designed according to the priorities of funding agencies rather than the realities they aim to transform. Freidenberg (2022) likewise calls for hemispheric dialogues that foreground shared expertise and collaborative authorship rather than unidirectional forms of translation.

Ethnography became a slow, attentive practice of stitching together insights from actors positioned very differently across the implementation chain. These stitches did not eliminate structural inequalities but made them speakable and visible to those able to adjust strategies, resources, or priorities. They allowed concerns that often remain unvoiced—exhaustion, institutional constraints, uncertainties—to circulate in spaces where they are rarely acknowledged.

By the end of the project cycle, implementation resembled a shared fabric woven through collective listening and iterative translation. Ethnography acted as both needle and thread, connecting and at times repairing relationships within a complex, multi-scalar environment. Rather than offering definitive solutions, it practiced a form of situated justice, one woven through ongoing attention, relational work, and the creation of spaces where realities could be articulated and contested across the global–local interface.

[1] All references to organizations and agencies have been anonymized to protect those involved. I thank the NGO for offering a space to rethink applied practice, as well as the project coordinator, the area coordinator, the NGO director, and the colleagues working in territory for their guidance and collaboration.

[2] The Fair is located in Lomas de Zamora, Province of Buenos Aires. To read more about La Salada Fair see https://www.revistaanfibia.com/la-salada-es-para-siempre/ .

References

Freidenberg, Judith Noemí. 2022. “Applied Anthropology in Latin America: Towards a Hemispheric Dialogue.” Human Organization 81 (2): 101–10. https://doi.org/10.17730/1938-3525-81.2.101

Hale, Charles R. 2008. Engaging Contradictions: Theory, Politics, and Methods of Activist Scholarship. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Holmes, Seth. 2013. Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies: Migrant Farmworkers in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lassiter, Luke Eric. 2005. The Chicago Guide to Collaborative Ethnography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Moya, Marian. 2016. “Presentación: Antropología aplicada: del recurso utilitario al compromiso para la transformación”, Etnografías Contemporáneas, 1(1). https://revistasacademicas.unsam.edu.ar/index.php/etnocontemp/article/view/13

Mosse, David. 2005. Cultivating Development: An Ethnography of Aid Policy and Practice. London: Pluto Press.