Building Up: An Ethnographic Approach to Campus Planning for Climate Futures

Jake Culbertson, Bryanna Benicia, and Scott Cryer, HGA Architects & Engineers

Affiliation:

Jake Culbertson and Bryanna Benicia are ethnographers in the Design Insight Group at HGA Architects & Engineers, with advanced degrees in Sociocultural Anthropology and Engineering Design Innovation, respectively. Scott Cryer is an architect and Principal at HGA specializing in museums, performing arts, and higher education projects.

Keywords

Climate futures; climate adaptation; design thinking; iterative ethnography; community design

Methodological Takeaway:

“Our ethnographic practice rarely stops with documenting perspectives. In conjunction with Design Thinking methodologies, ethnography becomes a mode of invention (not just discovery, cf. Venkatesan et al. 2013), devising concepts that invite workshop participants to push past assumptions and imagine freely. This iterative feedback loop enables ethnography-driven design to build up over time. The outcome is a more incisive, thoughtful, community-grounded design. But along the way, it builds rapport enabling honest exchanges, creative confidence to tackle challenges, and visions for the future—even decades down the road, in different environmental conditions—that guide present work.”

On a morning in early spring 2025, the Board of Directors of the Mystic Seaport Museum gathered in a stout brick building on the banks of the Mystic River, adjacent to moorings for small sailboats. In a conference room, the directors stood around a site plan of the Museum’s nineteen-acre campus, mounted on poster board and perched on an easel.

The Mystic Seaport Museum is one of the world’s preeminent maritime museums, with exhibit halls, event spaces, a restaurant, a preservation shipyard, vast research archives, a replica nineteenth-century “seaport village,” historic and replica sailing ships, and the many buildings that support the Museum’s operations and visitor experiences. It also has a mounting problem with tidal flooding, which inundates a quarter of the campus a few times every winter and spring, when ice flows down the river to meet rising sea levels from the Long Island Sound, just three miles to the south. The Museum has more than a hundred buildings of all sizes and in various states of repair. Most of these have not been inundated by the river, but the whole campus is impacted by the ways that flooding can reconfigure the experiences of visitors and the daily work of staff with little notice.

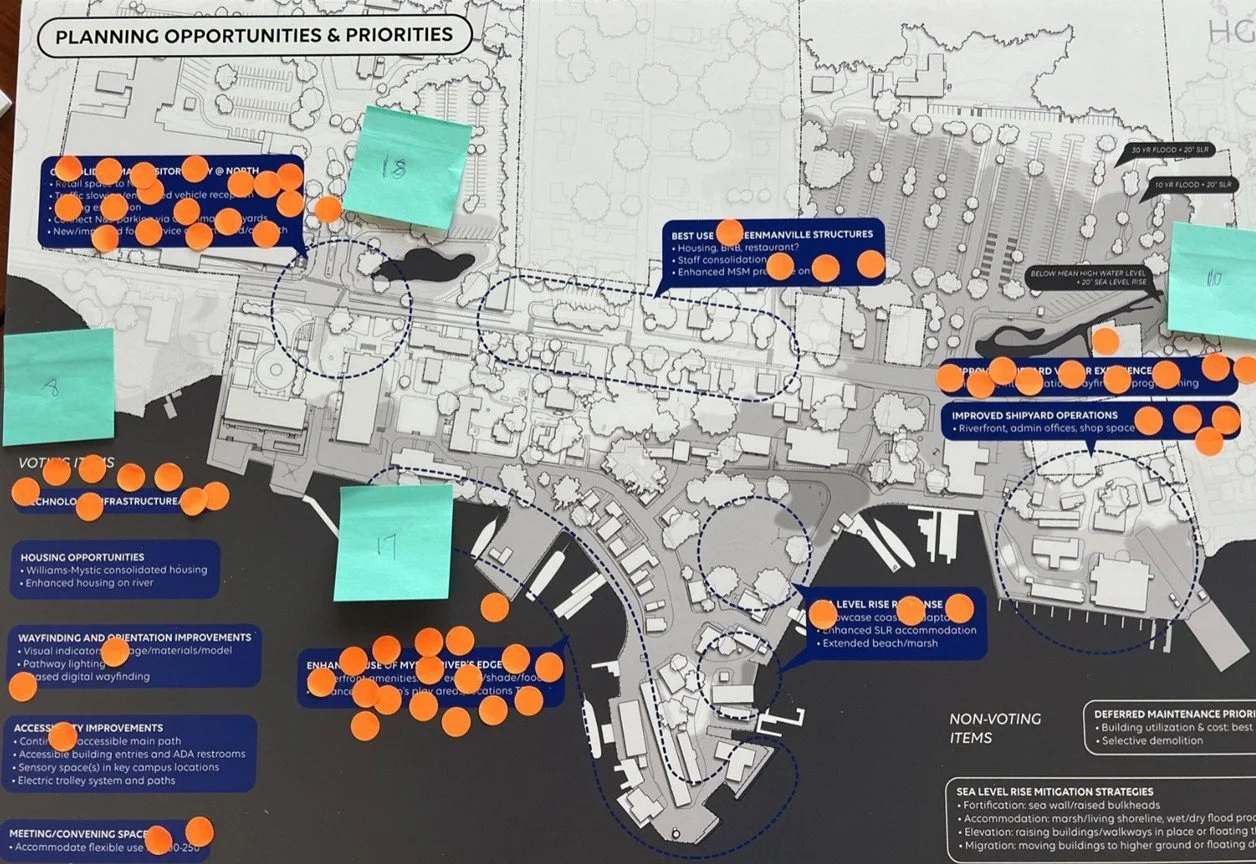

A site plan is an architectural document that shows the layout of buildings, landscape features, utilities, and other infrastructure, drawn to scale as if seen from a bird’s eye view. The purpose of this particular site plan, and of the board meeting gathered around it, is to decide upon a set of possible tactics to mitigate the flooding in a way that is consistent with larger strategies for institutional growth. In other words, this site plan is a tool for planning to deal with rising sea levels by visualizing competing priorities: consolidate the north entry, improve the visitor experience in the shipyard, and enhance the use of the river’s edge. Each has its relative costs and benefits, and it would be entirely too expensive and disruptive to take them all on at once.

The extent of future flood scenarios is indicated on the site plan in greyscale, positing a twenty-inch rise in sea level by 2050, with darker splotches signifying deeper water. At that level, a ten-year flood would cover most of the campus. Various ideas for moving, raising, or improving dozens of buildings that are subject to flooding are also plotted on the plan with word bubbles and dotted lines. The board was asked to vote on these by placing orange dot stickers directly on the plan. Clusters of orange dots signify the priority of infrastructural interventions that will unfold in phases over at least the next decade.

Board members vote with orange dots on 11 planning priorities, May 2025. The map shows buildings, projected flood zones (greyscale), and necessary and optional interventions—the culmination of 18 months of participatory research.

This voting exercise stems from the simple premise that the river now poses a threat to the Museum. Yet the river's social and hydrological life is integral to the Museum's mission, atmosphere, and offerings. The southern campus is built over an estuary where hundreds of ships were constructed through the 1800s, using tidal flows to float vessels into the river. Victorian sea captains' houses line both riverbanks, their presence forming both context and main attraction.

Beyond welcoming a quarter million annual tourists, the Museum hosts weddings, corporate retreats, lectures, film showings, and festivals. Members come for riverside walks, playground visits, or picnics on the green. These offerings leverage the maritime atmosphere created by historic buildings, vessels, and shipbuilding technologies—and the river's proximity, which now encroaches on campus grounds. The same structures—the original ropewalk, coal-fired steamboat, last remaining wooden whaling ship, printing press, iron forge—host school groups, the Sea School for aspiring mariners, and vocational training in maritime trades.

These programs signal directions the Museums hopes to grow, supporting research into maritime history and giving back to the local community. They are threatened by the rising tides but, with strategic foresight, may also be propelled by them.

This site planning project rests on an “infrastructural inversion” (Bowker 1994)--the practice of “turning inside out” a building project to reveal the social relationships, values, and practices it entails. Ethnography entails seeing building projects as inherently social in their motivations and consequences. Once the museum-river interface is understood in social (rather than purely hydrological or infrastructural) terms, social analysis can be inverted into technical and organizational strategies.

The point is to merge social and infrastructural knowledge into integrated solutions that address flooding's disruption of museum operations (now and next winter) while enabling museum futures to emerge through design concepts for managing the swelling river (time horizon: 2050). Environmental planning alone won’t suffice. You need ethnography.

Winter flood event at Mystic Seaport Museum. These occur multiple times annually and will intensify with sea level rise, threatening infrastructure and irreplaceable collections.

A Phased Approach

HGA Architects & Engineers began working with Mystic Seaport Museum in 2023 when the President commissioned Scott Cryer, a Design Principal with expertise in campus planning and museum design, to make sense of existing flood mitigation proposals. Multiple firms had concluded that tidal flooding poses a significant threat requiring millions in improvements. All shared the same shortcoming: they presented recommendations as a single flood-resilient future—a fixed destination, undifferentiated by timing, priority, or cost. They offered complex, long-term solutions without roadmaps for getting there.

HGA's task was to reconcile these proposals into a phased approach, but sequencing these projects isn't just logistical. It hinges on subjective questions about the Museum's priorities: what to protect from flooding, what to disrupt with construction—questions of values, operations, mission, and visitor experience. With this in mind, Cryer engaged HGA's Design Insight Group, an in-house team of environmental design researchers including ethnographers, to gather insights from visitors, staff, and the Board.

Those initial engagements would prove to be the first steps in an 18-month project that featured ethnography in two ways. First, we used ethnography as a method of empirical data collection, conducting interviews and surveys to gather “stakeholder” perspectives. Later, ethnography figured as a mode of conceptualization for developing and refining a series of “design visions” (cf. Drazin 2020). In both senses, ethnography featured as ways of listening and thinking within a broader methodological framework of “co-creation” drawn from the field of Design Thinking, proceeding through four phases of engagement that we called Discovery, Sensemaking, Ideation, and Prioritizing. This methodology, in general, and the contingencies of the Mystic Seaport project in particular, demonstrate one way that ethnography can collaborate with design to devise complex technical solutions that arise from listening to and working with diverse “affected publics” (Barry 2013), building up iteratively through shared exploration and feedback. In this case, this methodology serves as the infrastructure of ethnographic engagement from which the material infrastructure of flood mitigation emerges (cf. Strathern 2018).

The first phase of the research, the Discovery phase, sought to understand how different groups see the campus, in all its colorful complexity. This data would convey an empirical picture of the current state of the Museum, from which we would formulate more speculative, aspirational questions in subsequent phases. Using Maptionnaire, map-based survey software, twelve hundred participants linked their ideas and experiences to a diagram of the campus. Four sections asked participants to identify meaningful areas ("Patterns"), map their visit routes ("Paths"), suggest future improvements ("Ideas"), and rank possible priorities ("Priorities"). The resulting heat maps revealed patterns of experiences, values, and preferences, showing which areas are most loved, impactful, or in need of attention.

In the Discovery Phase, a heat map visualizes concentrations of memorable visitor experiences on the museum campus.

At the same time, DIG conducted a series of semi-structured group interviews with the Museum’s Operations, Education, and Visitor Services Departments to hear directly from them about the reach and impact of flooding, as well as their specific ideas for institutional growth: a new home for the maritime jobs training program; a permanent auditorium for films and speakers; a reliable lunch space for school groups when it rains; a safe, accessible, curated route through the working shipyard for tourists, just to name a few.

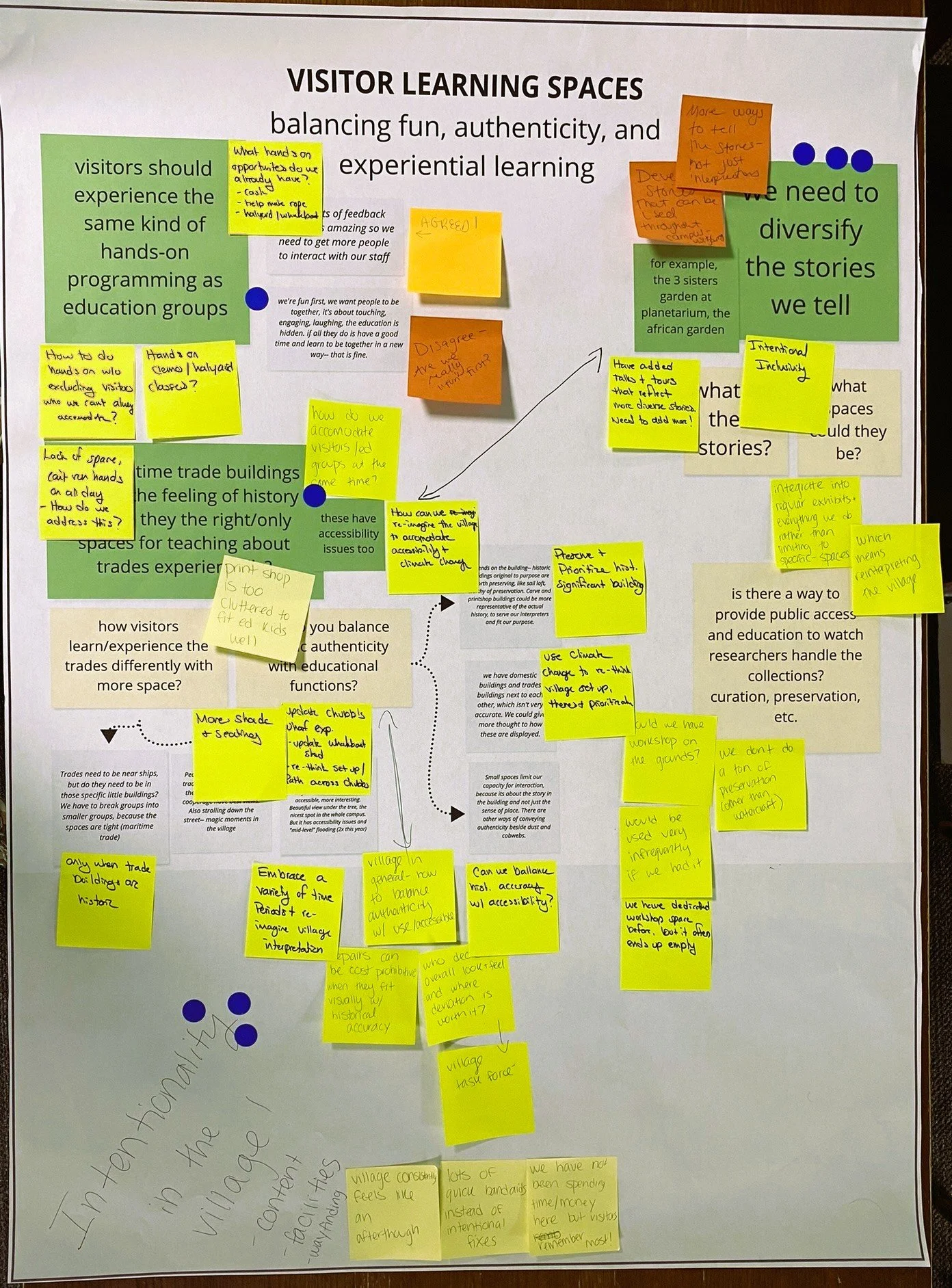

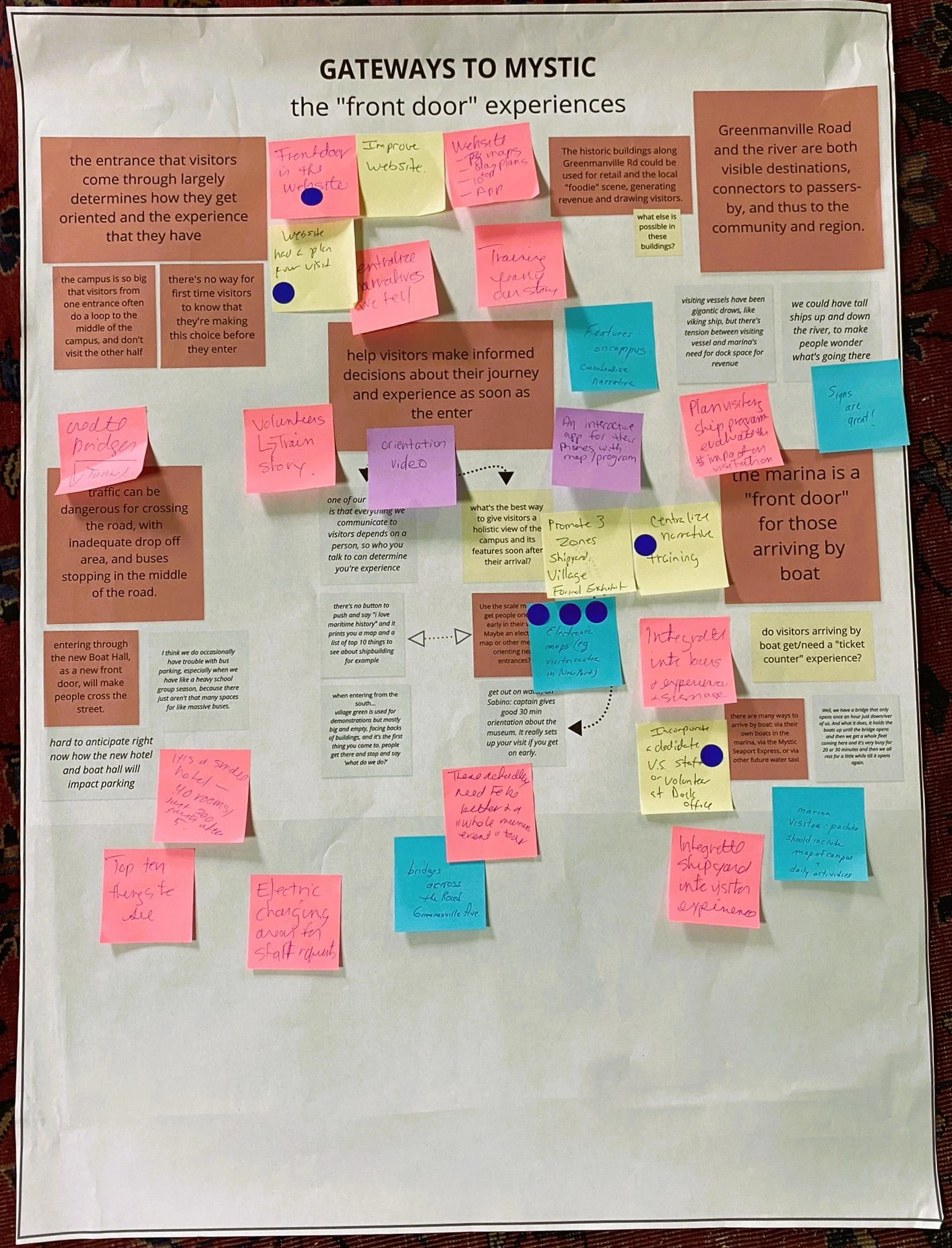

For the second phase, Sensemaking, we organized all this survey and interview data into ten broad categories, or “themes,” that we understood to represent the main areas of interest, concern, and opportunity for how the Museum will evolve, weaving together long-standing initiatives, routine maintenance and upgrades, bold new ideas, and the emerging consequences of the river spilling over its banks. The themes were deliberately broad, even abstract: “The River’s Edge,” “Learning Spaces,” “Playscapes,” for example. The point was to give conceptual order to the heterogeneous collection of data patterns and narrative descriptions that we had gathered about how the campus operates now and in the future.

Those ten themes were the basis of the Sensemaking Workshop, our first on-site cocreation event in the summer of 2024. Each theme was presented on a poster with supporting data points and questions that were intended to expose and address gaps in our knowledge as outside consultants. Twenty-eight members of the museum staff, drawn from all departments and levels of seniority, joined in a “sensemaking” exercise, in which they discussed their own interpretations of the research findings, noting what they found revealing, surprising, or incomplete, and making suggestions about how we could account for those insights in developing the campus’s site plan.

In the second phase, theme boards presented data to staff for their “sensemaking.”

The third phase was Ideation, in which we invite workshop participants to think freely and boldly about the challenges and opportunities that they face, unencumbered by practical considerations like cost, timing, feasibility, coherence, or even physics. Ideation employs a different way of thinking than sensemaking, which is about understanding empirical reality as clearly and concretely as possible. Ideation is speculative and experimental, concerned with brainstorming, with pushing open assumptions about what is possible, and chasing after innovative out-of-the-box solutions that often emerge from uninhibited collective creativity. At minimum, it provides another layer of ethnographic insight into the logics and motivations through which they understand the project. But it also enacts our conviction that the users of the spaces that we design are best positioned to invent the solutions to their own problems. Real design ideas come out of ideation workshops all the time.

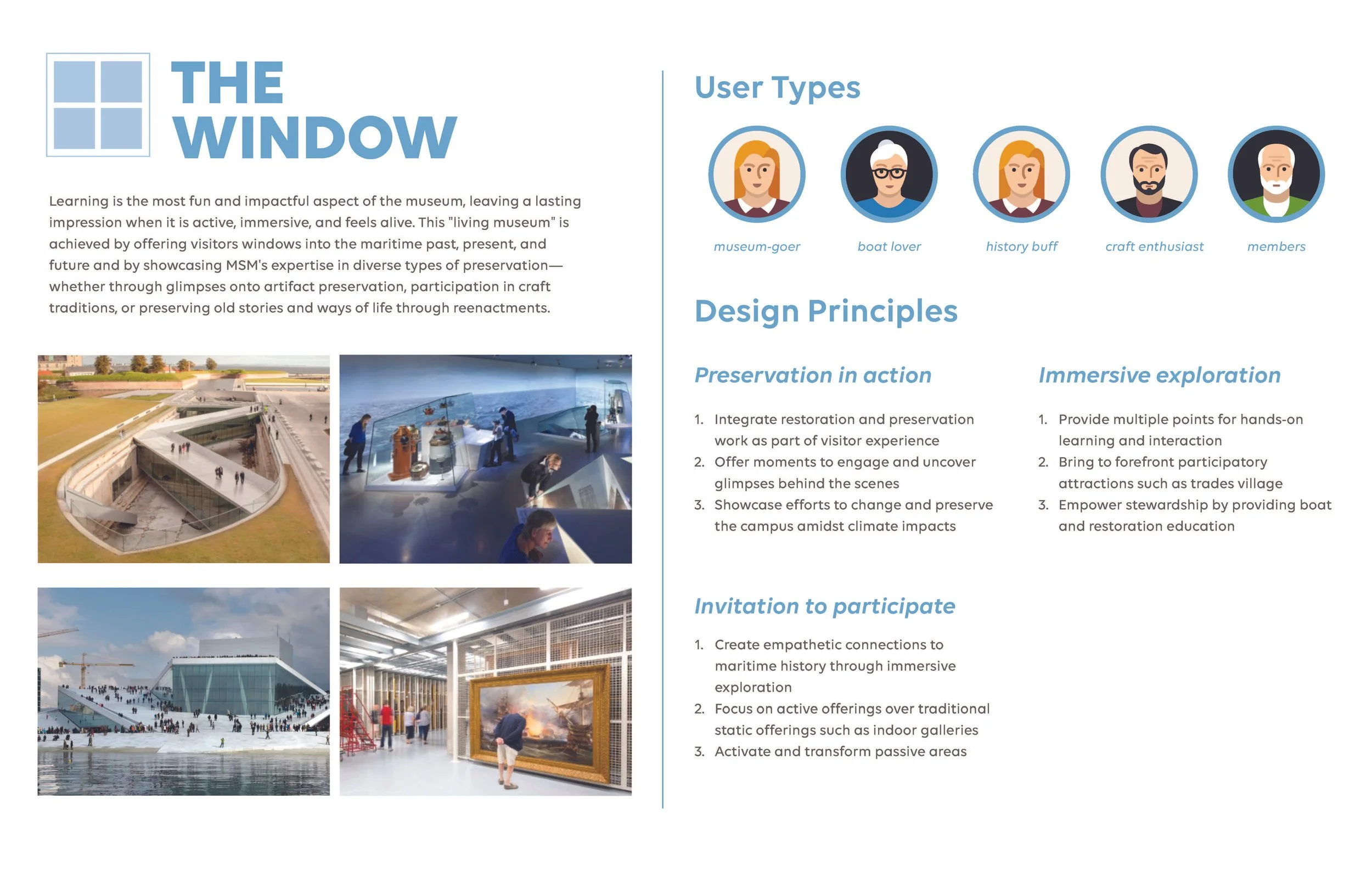

In the spring of 2025, we gathered again at the Museum for an Ideation Workshop. We assembled the same cast of Museum staff and led them through a new set of three “visions,” this time detailed on handheld placards that were easy to pass around a table. Each placard expressed a divergent vision for the Museum that had emerged from the Discovery and Sensemaking phases. Crafting these three involved a lot of our own creativity, digesting the accumulated data, and inventing design concepts that were supported by data but also formulated to push them beyond familiar ways of envisioning the Museum’s future. We called them “visions” because we wanted the participants to view the Museum through them, as if colored lenses.

Vision 1, The Window, focused on immersive, learning experiences for visitors and showcased the Museum’s expertise in historic restoration beyond its curated collections. Vision 2, The Seaside Village, catered to those who like to gather, celebrate, or relax in a beautiful historic atmosphere, albeit without directly experiencing the Museum’s collections. Vision 3, The Maritime University, prioritized hosting academic researchers and conventions that leverage the Museum’s prominence in New England and maritime histories.

In reality, all three visions are already integral to the Museum and present on the campus to some extent, and our campus plan balances these as core to their mission. For the Ideation Workshop, though, we divided the staff into three groups and tasked them with realizing the one specific, narrow vision that they had been assigned, as if they would put all their energy and resources into that one direction for growth. What would it mean for this to be a Seaside Village? How can we become the world’s leading maritime restoration museum? What if we turn into a Maritime University? What priorities, activities, and types of visitors would feature most prominently if this particular vision were achieved?

For the Ideation Workshop, three groups were each given a vision placard to explore and realize through brainstorming and gameplay.

At the start of the workshop, each of the three groups received a deck of cards that we had created to accompany the placards. The cards asked what we call “’How Might We’ questions” that inspire brainstorming around the components (or “Design Principles”) of each vision that were listed on the placards. How might we provide flexible classrooms to cater to diverse ages, group sizes, and activities? How might we create intentional relaxation destinations by the water? How might we reimagine the shipyard as a visitor experience without getting in the way of workers’ day-to-day function? Participants scrawled their ideas on post-it notes with sharpie markers and discussed them with each other, standing and circling their tables, passing and placing these notes in overlapping clusters as overlapping ideas emerged. Creativity is an embodied, material practice.

When brainstorming slowed, we transitioned to the main event: a board game where participants would collectively turn wild ideas into viable planning strategies. The point was to see how they would navigate compromises and competing imperatives with limited space and resources, revealing personal and institutional priorities as well as interpersonal dynamics.

The gameboard used the same site plan from the board meeting, with future flood forecasts indicated. Players had two resources: their post-it note answers and finite tokens. Guided by their vision placards, they used tokens to indicate which buildings to renovate, relocate, demolish, or add. Players quickly realized that placing tokens was easy; making everything fit while accounting for flooding, balancing priorities across seven players, and reaching agreement was far more complicated.

Staff negotiate building placements during the board game, which used finite tokens to force prioritization and surface tensions between flood protection and institutional aspirations.

Visually, the gameboards were a mess– groups borrowing ideas on post-its from each other and drawing with dry-erase markers to draw what tokens couldn’t. One group prudently solved for sea level rise; another proposed a multi-million-dollar bridge over the highway entrance.

Such divergent ideas revealed underlying values and assumptions. What does it mean to "save" the Museum? Which elements of its identity are non-negotiable versus adaptable? The game generated debate, identified consensus, and allowed us to see from their perspectives—their hopes, worries, risks, opportunities, and passions.

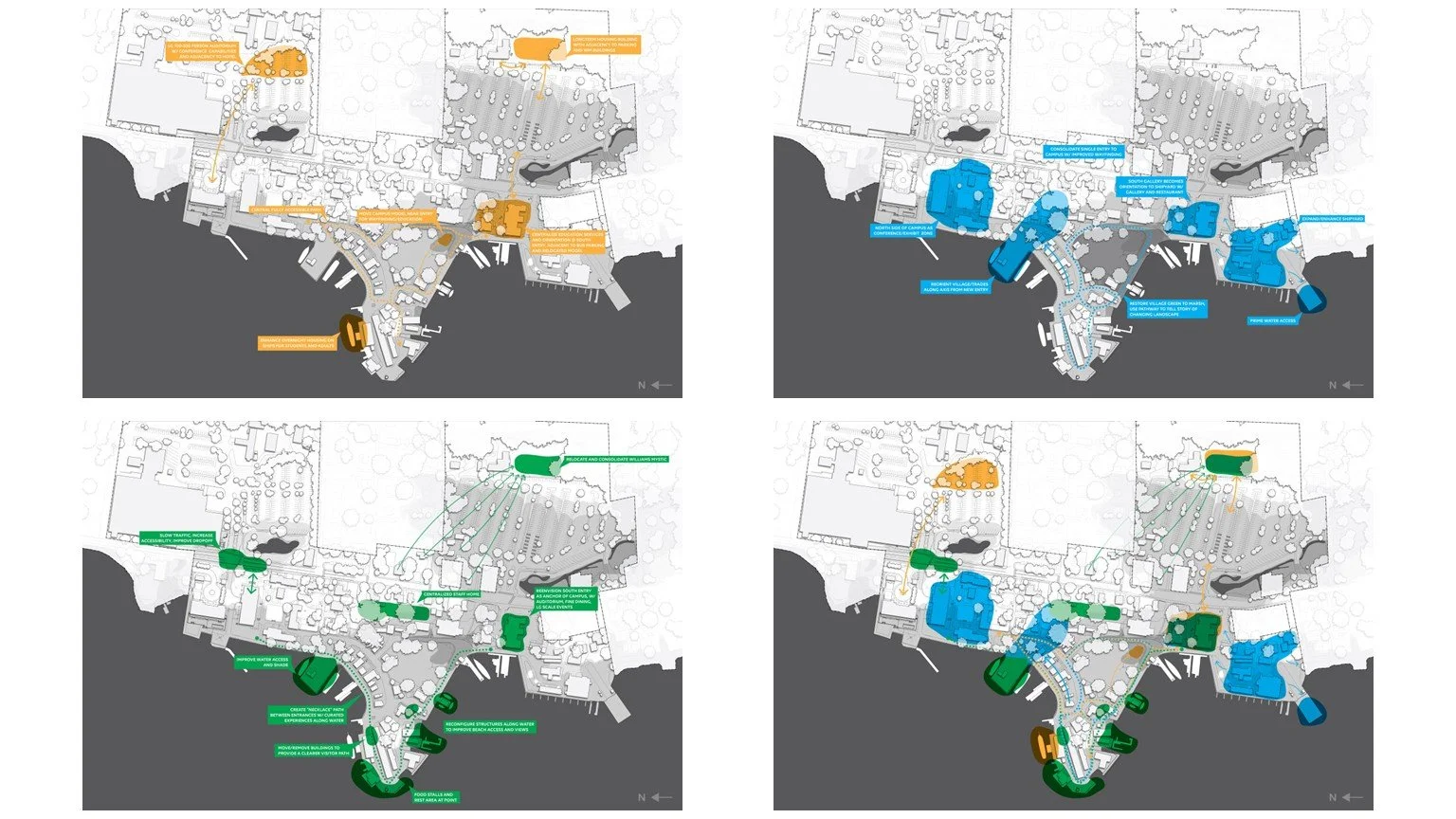

Each gameboard expressed dozens of possible design interventions; it wasn’t even clear how to count them. But larger ideas and clusters of ideas emerged as integral to realizing the visions that they were assigned. When combined, as if overlaying each other, these plans in three different colors show some similar areas of focus, some priorities that can realistically co-exist, and a few scenarios that are simply incommensurable. That overlay was sufficient to get hundreds of ideas down to eleven concrete priorities.

Three "extreme scheme" visions shown individually and in overlay. Darker areas indicate consensus that informed the 11 board priorities; divergent areas revealed incommensurable institutional futures requiring choice.

The final "Prioritizing" phase presented these 11 design projects to the Board of Directors, representing insights from over a thousand people and hours of ethnographic research. Like their colleagues, the Board engaged in evaluating and debating planning priorities to reach consensus on sequencing.

The board received the same map from the Ideation Workshop, now with eleven interventions appearing in blue word bubbles: improving the shipyard visitor experience, repurposing Victorian houses as shops or restaurants, enhancing the river's edge for education and recreation.

Each board member was assigned a finite set of orange dots. Much like the tokens, members used the orange dots to “vote” on the various interventions, expressing their assessment of the relative priority and feasibility of each project. By the end, the team could visualize an emerging long-term strategy for sea level rise that was still daunting and inevitable but also increasingly defined and manageable.

But what all the participants—designers, ethnographers, staff, and board members alike—can see that is not visible on the plan is that the 11 options can be unpacked into countless other ideas for how the Museum can and must evolve. Some of these are urgent and inevitable. Some are contentious, some whimsical. Some are moonshots, for the Maritime Museum of the future. Some are impossible, and inspire new ideas, new debates, about how things will change as the water continues to rise.

Ethnography as Environmental Design Practice

All built environments, whether architectural, infrastructural, or cultural landscapes, are necessarily social, as artefacts of the ways that people give order to their lives, materially and conceptually. The Mystic River is also a built environment, with flood plains that have been successively remade by many modes of human settlement, including 19th-century shipbuilding and 21st-century tourism. Consequently, built environments, including ongoing design projects, make valuable objects of ethnographic inquiry for how they reveal the passions and meanings invested in these spaces by people with shared and competing interests. From that perspective, environmental design is a means of doing ethnography as a genre of social analysis and critique. Considerable academic ink has been spilled on reading architecture and infrastructure projects for the public interest and the technoscientific fields of expertise that they entail. We draw on them in our work.

But we like to think that our work as ethnographers in an architecture and engineering firm demonstrates the opposite too–that ethnography is an important means of doing, and not just informing, the work of design. The two applications of ethnography described above speak to its value as a research method and as a disciplinary way of thinking. As a tool for understanding people’s values and motivations, ethnography’s comparative advantage over other research methods is in privileging the perspectives of one’s interlocutors, to learn to think with them, about their worries, their delights, their aspirations, rather than about them, in narrowly soliciting what design features they want and need (Lederman 2024). Or worse, confirming one’s own biases by only collecting answers to questions that you already thought to ask. Ethnographic inquiry is more open to surprise and nuance. For us, displacing whatever we think we already know is a mark of a successful research engagement.

Our ethnographic practice rarely stops with documenting perspectives. In conjunction with Design Thinking methodologies, ethnography becomes a mode of invention (not just discovery, cf. Venkatesan et al. 2013), devising concepts that invite workshop participants to push past assumptions and imagine freely. This iterative feedback loop enables ethnography-driven design to build up over time. The outcome is a more incisive, thoughtful, community-grounded design. But along the way, it builds rapport enabling honest exchanges, creative confidence to tackle challenges, and visions for the future—even decades down the road, in different environmental conditions—that guide present work.

References

Barry, A. (2013). Material Politics: Disputes Along the Pipeline. Chichester, West Sussex : Wiley-Blackwell. DOI:10.1002/9781118529065

Bowker, G. (1994). "Information Mythology and Infrastructure." In Information Acumen: The Understanding and Use of Knowledge in Modern Business, L. Bud-Frierman (ed.) London: Routledge, pp. 231-247.

Drazin, A. (2020). Design Anthropology in Context: An Introduction to Design Materiality and Collaborative Thinking (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315688732

Lederman, Rena. (2024). “Anthropology's comparative value(s).” American Ethnologist 51: 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.13229

Strathern, M. (2018) “Infrastructures in and of ethnography”, Anuac, 7(2), pp. 49-69. doi: 10.7340/anuac2239-625X-3519.

Venkatesan, S., Candea, M., Jensen, C. B., Pedersen, M. A., Leach, J., & Evans, G. (2012). The task of anthropology is to invent relations: 2010 meeting of the Group for Debates in Anthropological Theory. Critique of Anthropology, 32(1), 43-47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X11430873